“There was no doubt, they were hoping it would fail, I think they believed that in a couple of months we’d come back and say we couldn’t cope.” – Chief Commissioner Christine Nixon (2001)

ABSTRACT

The journey of women in policing and police leadership has been long and strewn with obstacles and issues. The aim of this chapter is to examine the historical background and cultural attitudes concerning women in policing in New South Wales as this is the largest police force in Australia and the experiences of policewomen in this organisation could be seen as broadly representative of the experiences of policewomen in Australia as a whole. It is understood that the attitudes to women in policing were often not just of the organisation and the individuals within it, but also have to be understood in the social and political context of the day and they cannot be viewed in isolation from this context.

The understanding of the historical detail of the journey of women in policing and police leadership, rather than just being a simple narrative, is important as it shows how the situation of today has been arrived at via the struggles and battles that were fought and the context within which they were fought. The detail is often lost in official histories that concentrate on the broader issues or provide a “sanitized” view of events, which is why this chapter is written from a personal, as well as historical, perspective. These issues have shaped the policing organisation and it is interesting to note that many of the issues were common to other police forces, both within Australia, and internationally. This is the critical message of this chapter.

Introduction

This chapter has been written not only to illustrate the history and struggle of policewomen in the state of New South Wales, Australia but maybe also to tell a story that is perhaps indicative of the barriers to acceptance and advancement of policewomen in many other police forces. So while it tells a story, it tells a story with a wider purpose. The issues faced by policewomen in New South Wales since they first joined the New South Wales police organisation in 1915, at a time of great social upheaval regarding role and gender issues during the First World War, are symptomatic of those generally faced by policewomen worldwide. There followed a second wave of upheaval in the Second World War leading to the Women’s Movements of the 1960s and beyond. So in a way the story of the changing role of policewomen is not only the story of women attempting to join, and be recognized, in a culturally male dominated profession but it is also aligned to the changing role of women in society generally and needs to be considered in the light of this wider social context.

I joined the New South Wales Police Force in late 1980, hence the start date for the main part of this study as it was a time from which I could make first hand observations. Although I did not know it then, it was the year that the quota system that restricted the number of policewomen in the Force to about 3% of total authorized strength, that had been in place since 1915, was finally abolished. We were not informed of this quota and I did not know the momentous changes that were taking place around me at that time. I was aware of a trainee policewoman by the name of Eileen Tompsett, in my class, who some Instructors told us was a trouble maker as she had taken legal action against the NSW Police Force in order to secure her place in our class, a heresy to them (NSW Police Association 1981 p7). In 1980 the number of senior female police officers in New South Wales could be counted on one hand. By the time I retired 25 years later the number of policewomen had grown from 3% to 25% of the authorized strength.

During my time in the Force I worked with many fine policemen and policewomen yet I became aware of some appalling acts of sexual discrimination and harassment by a minority. Yet even though only a minority were actively engaged there also seemed to be an undertone of resistance to women in policing generally, especially when a policewoman received a promotion no matter how well deserved, over a policeman. The comment of “She only got that because she was a woman” and others less pleasant, were often heard. Having grown up in a household that was run very much on the lines of equal opportunity from my earliest childhood, I was left wondering why and how this could occur as it was beyond the scope of my experience and understanding at the time.

I also looked at the struggle that took place over that quarter of century in what were the formative years for policewomen in New South Wales, where they went from being a mere addition (a very valuable one, but an addition never the less) to being a critical part of mainstream policing strength. Not long before I retired in 2005, I had the experience of walking through a major country police station as an Inspector (Lieutenant equivalent) on a night shift and realised that my entire shift crew were policewomen and that I was the only policeman present. How times had changed. It is this change, together with the undercurrent of cultural resistance that I will attempt to relate and describe in its social context during the course of this chapter.

The story of women in policing in New South Wales is one of cultural change and resistance from both within and without, and in that sense it has much in common with the rest of Australia and the world. Policing has been traditionally seen as a masculine occupation and many barriers were placed in the way of women wishing to join policing. Police forces, generally, are conservative organisations that are designed to preserve the social status quo and as such, are not going to be leading beacons in social change. However, any discussion of the changing role of women in policing needs also to be considered in the light of the social norms of the day (More 2008). Policing is not an island and is impacted on by the same economic, political, social, technological and demographic issues that impact on the rest of society as a whole. To understand many of the leadership issues that face women in policing in the present day it is important to have an understanding of the historical and social background that created the current position.

The aim of this chapter is to discuss the advances of women in policing leadership roles in the New South Wales Police Force over the past 30 years, with some historical insights into the origins and developments since the first policewomen were inducted into the NSW Police Force in 1915. Yet these issues and advances must also be considered in the light of their broader historical significance and not be viewed in isolation from the perspective of the 21st Century and will be more fully examined in the course of this chapter. It is also intended to explore the implications for “leadership” and “followership” as these apply to women in New South Wales Policing.

Leadership is an activity not a position and achieves its effectiveness by influence. Without the necessary influence in the police organisation it has been difficult for women to perform leadership roles even after achieving the necessary rank. Also formal, rank based leadership in the traditional “Command and Control” culture of policing tends to be downward, whereas informal leadership can also be lateral and upward, but again influence is necessary to be effective in a leadership role. These are all issues that have impacted on the leadership role of women in policing generally as many women have found it difficult to exert the necessary influence in the face of cultural and organisational resistance, which is only recently started to change.

As previously noted, I joined the NSW Police Force in 1980 and was in a position to observe much of what happened prior to his retirement in 2005 having worked not just in operational policing, but in a range of training and educational roles as well. Also included will be personal insights from a number of policewomen, both serving and retired, who will add a human perspective to the story. In the body of the chapter it is proposed to use the terms “policewoman” and “policeman” when discussing female and male police officers in a gender specific context. This is not intended to be a sexist position but rather a descriptive term that was used as an official designation in the New South Wales Police Force until the early 1980s.

PART 1: The Historical Origins

Police Forces are not renowned for being at the forefront of social or organisational change. Things like discrimination and negative attitudes that seem to been at times unjust, or at least anachronistic, often having historical origins that are slow to change. To understand the leadership and gender issues facing women in policing today, it is firstly important to have some understanding of the historical context that has formed these issues. The past century has seen immense changes in the role and status of women in societies across the world and policing has experienced the impact of this social change and the experiences of women in the New South Wales Police Force are not unique, but this does not make the management of this change any less challenging for both the police organisation and the women who serve in it.

The story of women in policing in the New South Wales Police Force begins in 1915 with the induction of first two policewomen into the organisation. The New South Wales Police Force had been formed in 1862 from six functionally independent police forces operating in the British colony of New South Wales at the time. Australia became a nation after Federation in 1901, but has retained its state policing system with seven State Police Forces and one Federal Police Force. The New South Wales Police Force is the largest of these organisations with currently some 15,000 sworn members and 3800 non sworn members (NSW Police Force 2009). The Force remained a “male only” bastion until the beginning of the First World War with very little reason seen for change. Female crime rates in pre-war New South Wales were markedly low in comparison to their male counterparts, in keeping with the gender roles of Australian society of the day. In 1911 females were charged with only 9% of all offences in New South Wales. This proportion declined in the 1950s and 1960s before returning to this level in the 1970s (Allen 1987 p190).

The beginning of the First World War saw a range of social upheavals with women taking on more of a role outside of the home as male labour shortages caused by wartime recruitment saw the opening of work and social opportunities for women that had not existed before the war. These shortages of male labour applied in policing just as it did in every other occupation (Unstead & Henderson 1973 p88; Prenzler 2010). During the First World War over 416,000 Australian men volunteered for overseas service in the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF) out of a total population of some 4 million (about 38.7% of the entire male population).

However these openings were not uniform and in many ways, in Australian society, the male dominated culture reverted and was reinforced after the war ended. This was contrary to the British experience where the social change brought about by the war had much longer lasting effects with respect to the role of women in the workplace and broader society. (McQuilton 2001 p119). The social change and regression was to have significant effects on the role of women in Australian society over the next half century and may explain many cultural gender stereotypes that pervade Australian society, even today.

The move of women outside of the home saw a greater interaction between them and the agencies of law and order. With this came the need for female police to more adequately deal with this interaction. Indeed, in the British context there had been complaints for some time about the rough handling of female prisoners by male police and prison officers, especially during the Suffragette Period of a move for increased Women’s Rights. This saw the first policewomen joining the London Metropolitan Police in 1914 (Ainsworth 2000 p100). There were to be many interesting parallels between the deployment of policewomen in the London Metropolitan Police and policewomen in the New South Wales Police Force and these will be visited later in the chapter. Similarly there were pressures to engage women in policing in many other areas too. In the Australian context the South Australia police appointed its first policewomen in 1915, who contrary to most contemporary practice enjoyed full police powers and equal pay and conditions from the beginning, a precedent not followed in other states for some time (Clynne 1987). Victoria appointed its first policewomen in 1916, Western Australia in 1917, and Tasmania in 1918 (Owings 1925 pp58-60; Haldane 1986; Easton 1999). Queensland did not employ policewomen until 1930 (Johnston 1992).

After significant pressure from women’s lobby groups, over a period of 25 years from the 1890s, the NSW state government authorised the then Inspector-General (later Commissioner after 1926) of Police James Mitchell to allow the appointment in 1915 of Lillian Armfield and Maud Rhodes as “Special Constables” in the NSW Police Force from some 400 applicants (Nixon 1994 p74). This employment status for policewomen in New South Wales was not to change until 1965 when policewomen were finally employed on an equal basis to policemen, also gaining equal pay (an oddity at the time), but they had to wait another 10 years before they were finally integrated into the same seniority list as male police officers in 1975. The 1962 Centenary Booklet of the NSW Police Force makes the following reference to the employment status of policewomen:

“Women with special qualifications are sworn in as Special Constables under the provisions of Section 101 of the Police Offences Act of 1901, to carry out certain phases of Police duty. Upon appointment they hold the rank of Special Constable, but with seniority and outstanding ability can later rise to the rank of Special Constable 1st Class, Special Senior Constable and Special Sergeant.” (Hoban 1962 p110)

Policemen of the period were employed under a different Act, the Police Regulation Act of 1862. This conferred a completely different status on them under law as full Constables. The first Policewomen were not permitted to join the NSW Police Union, the NSW Police Association, until 1952, thus denying them any real Industrial representation until that time (Brien 1996 p100).

Another interesting feature of employment of Special Constable Armfield, which would be extraordinarily discriminatory in today’s industrial environment, was that she was not entitled to any Superannuation or Police Pension upon her retirement. In her original contract of employment, dated from the 1st of July 1916, she was specifically excluded from any injury compensation and pension benefits, even though during the course of her service she was awarded the Kings Police and Fire Service Medal for Distinguished Service in 1946 (the first woman to receive this honour) and later the Imperial Service Medal in 1951 upon her retirement after eventually being promoted to the rank of Special Sergeant 1st Class. This feature of employment continued for the 34 years that Special Constable Armfield remained with the NSW Police Force (Rhodes having resigned in 1920 relatively soon after her appointment) (Kelly 1961; Unstead & Henderson 1973 p88).

Policewomen in New South Wales were not to be entitled to police superannuation benefits until 1965, 50 years after the appointment of the first policewomen, although policemen had been eligible for superannuation benefits since 1906. In 1965 The NSW Police Regulation Women Police Amendment Act No. 64 of 1964 was proclaimed and the 58 policewomen of the NSW Police Force were at last employed on an equal footing as their male counterparts in regards to wages and conditions and given full police powers under law. Their title was also changed from “Special” to “Policewoman” It is also interesting to note that policewomen of this early period from 1915 were not issued with uniforms in New South Wales. Uniforms were not issued to policewomen in New South Wales until after World War 2. Nor were they generally issued with firearms until 1979 (Sutton 1992 p69). It was not until 1961 that they were permitted to stay in the Police Force if they got married, although they had to ask permission to remain.

Also, policewomen were created as a specialist branch of policing very much in the same light as the Water Police, the Mounted Police and later the Dog Squad and Airwing (O’Brien 1960 p172). Policewomen remained under their own separate office until 1981 when it was finally dissolved and the staffing and administration of policewomen devolved to the normal channels of the organisation (Sutton 1992 p69). They were also identified on a separate “Strength Statement” until at least 1980 which separated the numbers of male and female officers at all rank levels (NSW Police Association 1980 p31). From 1965 policewomen also had a separate seniority list to men (hence many policewomen sworn in prior to the mid 1970s carried Registered Numbers such as 131 and 218, when their male counterparts were carrying numbers such as 17143) and were obliged to differentiate themselves by using the title “Policewoman” or “PW” before their rank on departmental correspondence. This distinction remained until 1982 in spite of the fact that it had been made illegal to differentiate or discriminate on grounds of sex under the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act of 1978. Even when this was challenged it was a requirement of policewomen to identify themselves as women until about 1984 by using the indicator (f) for female after their name on correspondence, rosters and documentation.

The duties carried out by the first policewomen in New South Wales were also rather different to the duties carried out today. Firstly, policewomen did not engage in General Duties (routine patrol type) policing until 1976 and even then it was on an ad hoc basis until 1980 when Policewomen were allowed to go straight into General Duties after graduating from the Police Academy.

The duties carried out prior to this initially revolved around runaway girls, drugs and prostitution (Kelly 1961). The original instructions from the New South Wales Chief Secretary for the duties of women police read as follows:

“1.To keep young children from the streets, and especially at night. 2. To assist in the prevention of truancy from school. 3. To watch the newspapers and to put detectives on the track of those who are apparently endeavouring to decoy young girls by advertisements or by any other means. 4. To patrol the railway stations and wharves when long distance trains and steamers come in, in order to guard and advise women, girls and children who are strangers and have no friends waiting for them. 5. To patrol congested neighbourhoods, and to look after drunken women and to obtain assistance for their neglected children. 6. To keep an eye on houses of prostitution, and on the wine shops and hotels frequented by women of the town, in order to prevent young girls being decoyed and drugged with liquor or entrapped. 7. To protect women and girls in public parks and when leaving work in the evening. 8. To assist, when practicable, in enforcing the regulations concerning pedestrian traffic.

In addition to these duties, all inquiries in connection with relief matters, where it is desirable that the inquiry should be made by police in plain clothes, are handled by special women constables.” (Owings 1925 pp56-7).

For policewomen in New South Wales the intent and spirit of these instructions was to remain in place for the next 60 years. It was to be the 1970s before significant changes in the type of duty for the majority of policewomen was to become a reality (Prenzler 2010).

However, the value of these tasks was recognized and by 1925 there were 4 policewomen in New South Wales. The senior member was paid 18 Shillings and 1 pence per day and the others 15 Shillings and 1 pence (Owings 1925 p56). By 1929 the number had increased to 8. This number remained static during the Great Depression after 1929 but by 1946 the number had increased to 36. By 1962 there were 58 policewomen in the NSW Police Force with 28 being attached to plainclothes duties with the Criminal Investigation Branch charged with patrolling railway stations, amusement parlours, waterfront areas and parks to prevent juvenile delinquency and assist with the general welfare of youth. The remaining 30 belonged to the School Lecturing Section of the Police Traffic Branch with the duties of controlling pedestrian crossings outside of schools and school lecturing (Hoban 1962 p111). This type of school duty placed another restriction on policewomen, requiring them to take their annual leave during school holidays and not at other times that suited them, a restriction not placed on policemen (Brien 1996 p101).

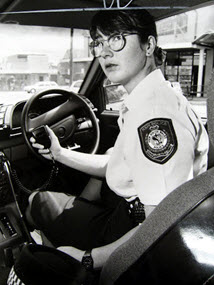

Policewomen had to rely very much on their personality and prior employment training. Armfield was a former Mental Health Nurse who joined the NSW Police Force at 31 and was noted for her high intelligence and physical strength. Training was scant, with policewomen not attending the same initial training course as policemen until 1958 when Janice Mossfield and Nellie Hobart were permitted to graduate in the same graduation parade with their 53 male counterparts in October of that year, although their training did not include any physical training, swimming or pistol practice (NSW Police News 1978; Nixon & Chandler 2011). Also, the first policewoman to be allowed to drive a police vehicle was not certified until 1957. It would appear from photographic evidence of the time that further training for policewomen was segregated and minimal.

This lack of emphasis on formal training for policewomen had an interesting and potentially dangerous side effect at a later time when policewomen were first integrated into general duties policing. I was to observe this at first hand when in 1982, I was transferred to a large country police station. One of the Supervising Sergeants was a senior policewoman by the name of Eileen, or “Aunty Eileen” as she was affectionately known to the male staff. She was something of a rarity as senior ranked policewomen in operational areas were not common. Her supervision style rested around sitting in the Sergeants office, knitting, and occasionally emerging to sign a duty pad or see what we young Constables were up to. She was a very happy and personable Lady and I was quite interested in this very “Laissez Faire” style of supervision and luckily Eileen was surrounded by competent junior staff who seemed to get the job done with a minimum of oversight.

I discovered that Eileen had joined the police in the early 1950s after her husband, a police officer, had died on duty. Eileen had spent all of her career in school lecturing, yet when policewomen were integrated into general duties policing from the late 1970s on, by virtue of her seniority and rank obtained under the seniority promotion system of the day, she was transferred to be a Supervising Sergeant at a large police station. She had no experience in general duties policing and having been minimally trained and experienced in operational areas, she was largely “lost at sea” in the operational policing environment and had no point of reference on which to draw. Hence the great interest in knitting during the shift.

This aside remains a funny and fond part of my memories as a young constable, and given the gentler social conditions of the day, we were able to get away with it. However, the ramifications of such Human Resource Management lapses are quite obvious. The police organisation had failed Eileen very badly by leaving her incompetent in the leadership and supervision situation in which she was placed by the organisation. This insight is in no way a criticism of Eileen but rather of the Human Resource practices of the police organisation of the day. In failing her in this way the organisation also failed us, her subordinates.

By way of balance it should be noted that the situation occurred with male Supervisors as well. When I was attached to my first police station I was well aware of a very angry Sergeant 1st Class, who used to take seemingly great delight in abusing any junior Constable who might be impertinent enough to ask a question. His main skill seemed to be in checking the books and counting the prisoners meal rations. I later discovered that he had spent his entire service in the NSW Police Pipe Band and had little concept of operational police supervision. His seniority and rank had eventually carried him into the position of Officer in Charge of a major metropolitan police station under the Human Resource practices of the day. His strategy to minimise scrutiny was to be so aggressive that no one would approach him. At least Eileen was approachable and personable and did not feel the need to portray a stereotype which made life a misery for all junior staff in the vicinity.

Yet there were also policewomen who made exceptional inroads into the male culture and forged impressive reputations even in the 1970s and 1980s. One such policewoman to show remarkable resilience and adaptability during her career was Inspector Irene Juergens. When she retired at the end of 2009 she was the longest serving Policewoman in the NSW Police Force, having joined the job in April 1966 as a Probationary Constable. Irene Juergens was one of those to be channelled into the investigations area, joining the Criminal Investigation Branch in 1972, and having served in many areas of operational policing including being the Sergeant in charge of the Crime Prevention Unit, she was appointed a State Coordinator of the Volunteers In Policing (VIP) Program in 2004 (Fisher 2010 p5).

This Program was trialled in 1993 with members of the community assisting Police as VIPs in such areas as victim support, distribution of crime prevention information and some general administrative tasks (Patterson 2008 p190). To date the VIPs have contributed 1.7 million hours of volunteer work in support of the NSW Police Force (Fisher 2010 p5).

The style of leadership required in this role was required to be very adaptable in that Inspector Juergens was leading a group of unpaid volunteers, who were resented by many of the regular constabulary in the early days as it was seen that the VIPs might take over some policing roles (this was never the intention). The VIP Program is now well established across New South Wales. I never met Irene Juergens personally but I was certainly aware of her name from my earliest career days, when she was a Plainclothes Sergeant and held up to us as a role model as a professional police officer. (Authors note – I am very grateful to Inspector (Retd) Irene Juergens for proof reading this chapter from the perspective of historical context and authenticity and adding her personal insights).

From the early days policewomen performed duty exclusively in Sydney, with the first positions outside of the state capital only coming into existence in 1941 in Newcastle, at the beginning of the Second World War in the Pacific. This, no doubt, was in response to the moral threat posed to the young women of Australia by the large numbers of U.S. Servicemen using Australia as a base. The posting of policewomen to country locations outside of the major metropolitan centres of Sydney, Wollongong and Newcastle did not occur until 1977.

The 1970s started to see a transformation in the role of Policewomen, and this should be viewed in the light of social change in the role of women generally (Bouza 1975; Nixon & Chandler 2011). The 1960s had seen the beginnings of a social revolution regarding the position of women in society, not just in Australia, but across the world. Women’s Movements began to force social change and this naturally flowed on to work organisations. With change came male resistance and backlash hence resistance from some quarters of policing was not to be unexpected (Austin 2000 p131). An understanding of some of what followed must be viewed in this light (Mackay 1993).

Another driver for change in this period was the landmark research study carried out between 1972 and 1974 by Peter Bloch and Deborah Anderson in Washington D.C. in the United States on behalf of the Police Foundation, entitled “Policewomen on Patrol” (Bloch & Anderson 1974; Thistlethwaite & Wooldredge 2010).

Prior to this study the position of Policewomen in the U.S. was little different to those of Australia or New South Wales, with only some 2% of police being female. In this study conducted in a large U.S. Police Department, the Metropolitan Police Department, it was evaluated across a range of mechanisms (including community surveys, supervisor reports, court results and statistical job performances) for the first time that policemen and policewomen had no significant performance differences in carrying out routine patrol work. There were also no real differences in job performance (including sick and injury report), attitudes, community reactions and capability. Policewomen were also less likely to be involved in misconduct issues and enabled the Police Department to be more representative of the community.

There were some dissenting views with arguments that the physical differences between men and women caused problems with women carrying out policework with fears that they may have to rely too heavily on their firearms to make up for lack of physical strength. It was also argued that the rigours of policing posed an “intense shock to the naturally gentle female system” (Mironowicz 1978 p391).

Change also came rapidly (for a police organisation) in the 1970s in New South Wales. In 1971 the first female detectives, Gwen Martin and Del Fricker, were accepted into training. Del Fricker had previously been awarded the British Empire Medal for Gallantry for her role in an arrest of a violent offender in 1963. However it took longer for policewomen to be accepted into some of the specialist detective squads. The first policewomen to join the Fraud Squad, Denise Herron and Verity Reardon, only started in that squad in 1982 (Police Association of NSW 1982 p13).For international comparison the first policewoman to serve with homicide squad in Hong Kong occurred in the same period in 1979 (Police Association of NSW 1979a p267).

In 1972 the first female Commissioned Officer, Inspector Beth Hanley, was appointed and Detective Inspector June Kelly became the first policewoman to hold that rank in the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB) (Police Association of NSW 1980a p7). In 1973 policewomen were permitted to marry and not have to seek permission to remain in the Force. In 1974 there was the granting of Maternity Leave and the issue of handcuffs, an interesting double act for one year.

The year 1974 also saw the admission of the first policewomen as Police Prosecutors when Barbara Galvin and Jacqueline Milledge joined the Prosecuting Branch. Barbara Galvin was later to become a Superintendent and one of the first Local Area Commanders after the 1997 reforms.

As previously mentioned policewomen were integrated into the same seniority list as policemen in 1975 and policewomen commenced to perform General Duties policing in 1976. This however was on a limited basis in Sydney with expectation that the policewomen would return to their normal duties after this temporary posting. The expectation of the organisation at the time was that policewomen would fail in the general duties policing role as it was seen as “a man’s work” (Brien 1996 p137). However, a group of policewomen sent to Darlinghurst Police Station (one of the toughest in Sydney) proved otherwise and this opened the door. This group included one Policewoman Constable Christine Nixon, later to be the first female NSW Police Assistant Commissioner in 1994 and the first female Police Chief in Australia, when she became Chief Commissioner of the Victoria Police in 2001 (Nixon & Chandler 2011).

This change of including policewomen in general duties policing roles had been forced on the NSW Police Force by the Australian Commonwealth Government signing the International Labour Organisation Covenant which discouraged workplace discrimination, especially against women. The then Commissioner, Mr Fred Hanson, attempted to put off the recommendations as they applied to the Police Force, but had to agree after the success of the Darlinghurst experiment.

Also in June 1977 the NSW Anti Discrimination Act No.48 took effect in New South Wales. This Act made it illegal for any employer or group to discriminate on grounds of sex, marital status, disability, sexual preference, religion or race. The Act was binding on the NSW Police Force (Duberly 1981 p1). An interesting comment is made by Wendy Austin, a serving NSW policewoman, (2000 p131) when she states that prior to the Equal Employment Opportunity legislation and policy harassment of policewomen (and women generally) was actually less, as they were not perceived to be a significant threat to the dominant male culture.

This “trial” situation continued until 1979 with a mention in the NSW Police News (the official journal of the Police Association of NSW) in April of the first policewomen performing general duties in the major metropolitan centre of Wollongong, just south of Sydney, during school holidays with the final comment “Sgt Hobbs said the three constables return to school lecturing when classes resume”. (Police Association of NSW 1979 p109)

Change continued at an accelerating pace with the quota for policewomen being raised to 145 in 1978 (the authorised strength of the NSW Police Force was about 9000 at the time). Policewomen were finally issued with firearms in 1979 even though policemen had been armed on a permanent basis since 1894 as a protective measure, although Lillian Armfield had been permitted to carry a pistol in the 1930s (Hoban 1994 p17). Female detectives had been issued with firearms in 1974 but this was not for general duties until 1979 and the “quota” that restricted female entry in the NSW Police Force was also lifted in that year. Perhaps the issue of firearms should be considered in context with the London Metropolitan Police which only permitted the arming of Policewomen in 1980 also. There was still an expectation that policewomen would be kept out of “harms way” though in many quarters (Police Association of NSW 1980b p7).

In 1980 policewomen were allowed to go straight to General Duties policing at police stations rather than be attached to the Police Training Centre or other body. Also the quota system, together with the policy of non acceptance of married women, was finally abolished after a complaint to the Anti-Discrimination Board of NSW by Virginia Carr, who was the first married woman accepted into the NSW Police Force in Class 166 of January 1980. This was followed by another successful appeal to the Anti-Discrimination Board of NSW by Eileen Tompsett, who was rejected by the NSW Police Force on grounds of marital status. Ironically she was married to a policeman. Women were now free to apply to join without having to be subject to numerical limits (Duberly 1981 p2). The Women Police Office was finally dissolved in 1981 and policewomen were now on an equal organisational and professional footing as policemen for the first time, in theory. The reality remained quite different for some time.

Change was hard fought even in the 1980s although progress was being made. 1980 saw the first policewoman attached to the Airwing as an Observer and the first policewoman in the Highway Patrol (putting this into a national comparison the first policewoman motorcyclist in Australia took up her role in the Northern Territory Police in 1980 (Police Association of NSW 1980c p7). In 1981 the first policewoman joined the Fingerprint Bureau, 1982 saw the first policewoman attached to the Mounted Police and 1984 saw the first policewoman diver and member of the Rescue Squad, although it was 1986 before the first policewoman was attached to the Water Police and 1994 before the first policewoman was attached to the Dog Squad (one of the reasons this particular phase of duty was resisted for policewomen for so long was on the rather dubious grounds that the dog’s sense of scent would be distracted during “that time of the month”).

In 1988 the first policewoman to become a Patrol Commander, Chief Inspector Bev Lawson took up her role at Engadine in Sydney. She was later to be the first female Deputy Commissioner in the NSW Police before her untimely death in 1998 while leading the reform of the NSW Police in the aftermath of the Wood Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service. She died of a stroke that was often attributed to the strain she was under at the time (Williams 2002 p227). In 1989 she became the first female Superintendent in charge of Wollongong Police Station and it speaks volumes for her leadership qualities that she was picked to be Deputy Commissioner to the new British Commissioner of the NSW Police, Mr Peter Ryan at a time of critical organisational change and reform after the handing down of the findings of the Wood Royal Commission in 1997.

I had great respect for Bev Lawson, based on an encounter in late 1995 when I was co-ordinating the Supervision Development Program at the NSW Police Academy. I was tasked to run a 2 week training course for Sergeants in Sydney on a “user pays” basis, some 200km from the Academy in Goulburn. I was to train some 20 Sydney based personnel over that period. I was given no budget or financial delegation to carry out this task.

After receiving a number of negative responses from several of police venues and senior police officers given the lack of finance, I happened to contact Chief Superintendent Lawson, who was then District Commander at Parramatta. Without hesitation she made available training rooms at one of her major police stations as well as clerical and logistical support. She had the insight to see the potential of what we were doing and the leadership sense to help make it happen. This was the first of many distance-based supervisory training courses that allowed for a greater access of staff to training. Her sudden passing, at a critical time, was a great loss for New South Wales policing.

In 1994 another benchmark was set when another well known policewoman, who was a detective working in the area of child protection, Chief Inspector Lola Scott became head of the Internal Affairs branch. She was later to become a Local Area Commander and work in strategic planning for the NSW Police before being dismissed in controversial circumstances in December 2002 as an Assistant Commissioner following Operation Retz, an investigation into her management style (a claim for unfair dismissal was subsequently settled by the NSW Police in 2004). At the time she was the highest ranking policewoman in New South Wales.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the easing of height restrictions in the NSW Police Force and the numbers of women in the NSW Police Force started to increase not only in actual numbers, but also in terms of percentage of whole strength. This was also coupled with a rapid expansion of actual authorised strength in the Police Force as well. In 1972 there were 130 policewomen in the NSW Police Force out of a total of 8630 police representing 1.5% of the total. This increased from 300 in 1980 to 307 in 1982 out of 9000 members (3.3%). In 1983 the number increased to 535 out of 9891 or 5.4%. The number rose rapidly to 720 in 1984, then to 883 out of 10765 in 1986 or 8.9% and 1086 in 1986 out of 11731 or 10.2%. 1988 saw a slight drop with 1217 policewomen out of 12176 members (9.9%) but this changed in 1989 to 1288 policewomen out of 12271 members (10.4%). By 1990 there were 1409 policewomen out of 12849 members representing 10.9% and in 1991 there were 1465 policewomen out of 13226 members (10.8%) (Nixon 1994 p76).

This also paved the way for many ethnic minorities to increase membership of the NSW Police Force. The first migrant policewoman, Johanna Suchy, had joined the job in 1957 but it was not until 1982 that the first indigenous Australian policewoman, Sandra May, joined and was stationed initially at Chatswood Police Station on the North Shore of Sydney, at the same time as me.

In 1992 there were 1465 policewomen in the NSW Police Force out of 13030 members (12.6%). By 1995, only 15 years after the quota system was abolished, when policewomen celebrated “80 years of Women in Policing” in New South Wales, there 1719 policewomen in the New South Wales Police Service (the title had changed from “Force” in 1989, although it was to change again in 2002 to “NSW Police” and back to “NSW Police Force” in 2007). A study of gender equity between 2003/4 and 2007/8 showed a steady increase in the ratio of policewomen rising from 24.52% to 26.38% (Prenzler, Fleming & King 2010)

On the 17 December 2009, there were 15714 sworn officers in the NSW Police Force of who 4169 were policewomen, representing 26.53% of the total (source: NSW Police Force Workplace Equity Unit). Things had come a long way since 1972 but not as far as the projected hopes of the 1990s. In 1995 there was a stated target of 43% of authorised strength were to be policewomen (Sutton 1995a p3). This has yet to be achieved. By comparison in the United States, policewomen made up about 8% of overall strength in 1990. This increased to 13% in 2001 (Thistlethwaite & Wooldredge 2010 p118).

At that time in New South Wales, the majority remained in the junior ranks. In 1992 there were still only 37 policewomen of, or above, the rank of Sergeant and given the historical context of day that would be expected. However, a study carried out between 2003/4 and 2007/8 showed that policewomen were becoming increasing successful with promotion applications over that period (Prenzler et al. 2010).

Coupled with this disparity of policewomen achieving promotion as opposed to actual numbers in the organisation, are a number of factors that emerged in a series of studies carried out in the mid 1990s. Whilst 70% of policewomen indicated that they regarded policing as a long term career when they joined, this tapered off quickly in the first few years to 47% (still a significant number). However there were also differing attitudes to promotion, although it was an important consideration by a majority of policewomen, yet only a relatively small number had applied for promotion by 1995 under the merit based system of the day (Sutton 1995a p38). This was coupled with why policewomen wanted to be in the police e.g. to make a difference and help people whereas policemen tended to cite the excitement of the job or career prospects (Sutton 1995a p10).

There was no lateral entry into the NSW Police Force at the time, which meant that no senior appointments could be made from outside and that all people joining the organisation had to start as a Probationary Constable (even in 2009 it is still very restricted to the point of being non-existent). Promotion prior to 1988 was on seniority and time in rank was still seen as a prerequisite under the merit based system that came in after that. A police officer joining before 1994 was required to serve 9 years before becoming eligible to apply for promotion at the rank of Senior Constable. This was reduced to 5 years after that date with promotion to Senior Constable coming down to that time frame after 1994.

Also, given the organisational policy prior to 1980 of channelling policewomen away from operational areas, where they could gain operational credibility and experience that would stand them in good stead for promotion, this weakened their position in the promotion stakes. This was still the case in some areas through the 1980s into the 1990s (Austen 2000 p131). Only time could fix this injustice of history, although by 2009 of the Senior Executive Service of the NSW Police Force i.e. sworn and civilian staff of the rank equivalent of Assistant Commissioner and above, 9 of the 29 members are women.

Uniforms, Appointments and Other Practical Matters

It would not be possible to consider the status of policewomen in New South Wales without considering the practical issues of uniforms and appointments as these reflect, de facto, many of the social attitudes of the day. As previously stated policewomen were not issued uniforms until 1948, prior to this all duties were carried out in plainclothes (Brien 1996 p98). This was a general rule throughout Australia with references as late as 1959 to policewomen in Tasmania performing duty with only a badge on the lapel of their civilian dress (Godfrey 1959 p205).

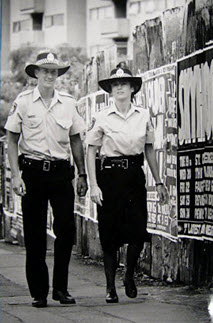

The first uniforms were issued to policewomen in New South Wales so that they could perform traffic duties when two policewomen, Amy Millgate and Gladys Johnson, were trialled in that role. (Millgate was later to be made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 1997 for her work with war veterans, having served with the Australian Women’s Army Service during World War II (Patterson 2008 p187)). The uniform consisted of the “feminised” version of the standard issue, dark blue, serge military style tunic of the day, together with a long blue serge skirt, light blue shirt and dark blue tie. Later, for summer wear a light weight, pale blue ‘A line’ dress was issued that buttoned up the front.

Inspector Irene Juergens recalled wearing the wool serge uniform in 1966. She informed me that at that time there were no female shirts and she was issued male Commissioned Officers shirts with detachable collars (Annual issue was 3 shirts and 6 detachable collars). She stated that the shirts were so big they doubled as a petticoat. On top of this she was issued wet weather gear consisting of a huge, black Motorcyclists wet weather coat. At the time she was “5’6” and 8 stone”.

The 1948 uniform was modernised in the late 1960s with the shortening of the serge skirt to above the knee. This was complemented with the issue of a new light blue summer uniform consisting of a short sleeved jacket and skirt (NSW Police News 1975 p304).

Also initially issued was the male style peaked cap, although this was shortly replaced by a more feminine broad brimmed felt hat. A narrow brimmed hat was later issued in the late 1960s as part of the new summer uniform. The ensemble was set off with a black leather handbag and court shoes. There was no provision for the carrying of appointments as none were issued.

In 1972 a complete new uniform was issued to the entire NSW Police Force consisting of a modernised tunic, trousers and cap for policemen and a female winter uniform of skirt, tailored jacket and a hat (the latter nicknamed the “tea cosy” or “flower pot” given its shape). The tie was replaced by a feminine “butterfly” bow tie arrangement. There was also a summer uniform of a light blue skirt and bowler jacket. Court or high heeled shoes were also issued, together with the ubiquitous black leather handbag. The handbag was later to be the repository for notebook, baton, handcuffs and gun when first issued, although a later issue of holster and handcuff pouch resolved this safety concern (Nixon & Chandler 2011).

Irene Juergens still fondly remembered her police issue handbag at her retirement 43 years after joining the NSW Police. “Officers today think it’s funny but in those days it was mandatory for everyone in the Women Police office to wear hat and gloves and carry a handbag. The police even supplied the handbag” (Fisher 2010 p5). She recalls even having to carry the handbag whilst in plainclothes as the bag held her appointments. What carrying a police issue handbag did for any attempt at anonymity one can only be imagined.

The skirts were of a tight cut, reflecting elegant female fashion of the day, which was fine for school lecturing or traffic duty but this presented a number of issues for Policewomen when they commenced patrol work. I am familiar with an incident in which a policewoman encountered a fence while chasing a “crook”. To solve the matter she pulled her skirt up around her waist to climb over the fence. An effective remedy but hardly suitable. One thing I can remember about the skirts of the day were that just about every one I observed worn by policewomen in general duties had torn stitching in the front pleats caused by the physical exertions of general patrol work in a uniform that was not designed for it.

These skirts were phased out in the mid 1980s with the issue of the more practical culottes. Slacks and trousers were not issued until the early 1990s, as they were not considered suitable female attire, no matter how practical the garment for operational policework. Also issued from the mid 1990s were blouses with pockets for pens and notebooks as the handbag was at last phased out.

Since this time female police uniforms in New South Wales have largely followed the male patterns with the exception of some tailoring details. Now, by and large, all Police personnel where the same shirts, cargo pants, GP boots and baseball caps for their day to day operational uniform. Some of the older distinctions are retained in the dress uniforms (e.g. the bowtie although the “tea cosy” was finally phased out in late 2010 being replaced by a kepi style cap) but these are the exception rather than the rule.

The service revolver, as issued to policewomen, also caused some consternation. Policemen were generally issued with the Model 10 Smith & Wesson 6 shot revolver with the NSW Police 3 inch barrel. Accurate to about 20 metres, this was a very satisfactory weapon for the operational needs of the time, before the proliferation of semi automatic handguns in Sydney street crime.

The revolver issued to policewomen, as it was believed that the Model 10 was too large for female hands, was the Model 36 Smith & Wesson 5 shot revolver with a 1 ½ inch barrel. The same weapon was also issued to undercover detectives and Commissioned Officers. The weapon was inaccurate at all but point blank range and its 5 shot capacity played havoc with annual pistol training and qualification as all the shooting sequences were based on 6 rounds. This meant that if policewomen were present on a range shoot, sequences had to be broken to permit them to reload to fire the set number of rounds and rapid shooting and reloading sequences required different procedures for policewomen issued with this weapon. Irene Juergens recalls the revolver “was just given to us”. She remembers failing an annual shoot due to the problem of trying to complete 6 round sequences with a 5 shot revolver and having the Instructor (male) taking great delight in telling all others present of her failure.

It would be interesting to determine how many other policewomen of the day also failed their annual qualifying shoot and were classified as useless with the service firearm, not through any failing of their own, but rather due to the failing of the service arm with which they were issued adding to the cultural perception of policewomen trying to do “a man’s job”. The operational implications for this situation were also quite dramatic.

The Model 36 was withdrawn from issue to policewomen in 1989 and replaced with the Model 10. With the issue of the Glock Model 17 .40 semi-automatic pistol after 1997 the same mistake was not repeated.

PART 2: The Cultural Hangover

The issue of women in policing generally seems to be one of gender clash impacted by the role of women in society generally. Several authors discuss the resistance to women in policing, organisational resistance and discrimination that exists even to the present day (More 2008; Chan, Doran & Marel 2010). Why there is still discussion over the suitability of women for the policing role after a century of demonstrated effectiveness is somewhat of a mystery. But it does show that the New South Wales experience is not unique.

The following quote well describes the cultural origins of policing organisations as they have existed in all areas for the past 200 years:

‘Police organisations have been set up by men, for men. Their values, functioning, culture and processes are ones that fit with many men. They are not organisations which allow women to operate within them and still retain their own female style. Too often, women must learn to operate as men to succeed and survive’ (Tynan & McDermott 2000 p243).

Any leader, manager or supervisor will know that the hardest thing to change in any organisation is the culture, or the way people behave within that organisation. The culture is often the paradigm for success in the past and therefore is perceived to be the paradigm for success in the future. Numerous change management activities have failed because they have failed to address this reality as it is also true that people do not resist change, but they resist being changed. It is easy to restructure an organisation and retitle individuals and groups, but until the mindsets and behaviours within an organisation change, nothing really changes. There are powerful forces within any organisation that has a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, past success and power often are derived from it and police organisations are based on power and tend to be more conservative than most and this is the great challenge in reforming and changing police organisations worldwide.

Changing an organisation with this paradigm and an old strong culture is not easy and has to be approached on many levels. Changing the culture of an organisation such as this is a slow and considered process taking in the people, processes, structure and technology as a complete entity. Many reform agendas have failed in the past by not recognising that reality.

Chan (1997 p61) states that changing culture is not just a matter of changing recruitment policies. As she points out women recruited into such an organisation adapt to survive and they adapt in one of two ways. Firstly they adapt by embracing the existing police culture and become “defeminized” as police-women or they take on the traditional service role allocated by the culture to become “deprofessionalized” as police-women. I would dispute this generalisation to some degree from personal observation of successful female leaders in the NSW Police Force. Those with which I have had personal dealing i.e. then Chief Superintendent Bev Lawson, Assistant Commissioner Christine Nixon and many others at all levels, were not defeminised or deprofessionalised, they were strong personalities who were very conscious of their gender and did not attempt to imitate their male counterparts or be “shrinking violets” in the workplace.

To read the officially sanctioned literature of the 1960s and before, one could be forgiven for thinking that the situation of policewomen in New South Wales was one of unremitting paternalistic joy, with policewomen contented with their lot. Policewomen had their place lecturing schools, directing traffic and assisting in some investigations where a woman was needed (Hoban 1962; O’Brien 1960). They represented no threat to the promotional order or the white, Anglo-Saxon, masculine, paramilitary culture of the organisation (Chan et al 2010).

Even contemporary material supporting the role of policewomen now appears paternalistic, quaint and out of another time. In an article published in the October 1975 edition of the Australian Police Journal, a former Assistant Commissioner of the Queensland Police puts forward a number of reasons why policewomen are “an asset to Law Enforcement” and bears quoting at length:

“At the present time some services, because of the increased amount of police work brought about mainly by the great upsurge in crime, have been compelled to recruit more women because men have not been available. This is bringing about a still further widening of the duties being performed by policewomen.

Women are proving invaluable to a police department on many types of assignments, including clerical duties, work in police staff units such as records, planning and research, front office contact with the public and radio dispatching.

Their services are also extensively useful in operational fields including patrol, vice investigation, undercover assignments, and other investigative services. It is not uncommon for a thief or a molester to suddenly find himself in the hands of the law and on the way to the watchhouse when he discovers that the woman he approached was a police officer with full power and authority – and ability!

Women have special value for maintaining a watch on suspected persons, or on property likely to be stolen, or at places where offences are frequent. No one thinks it unnatural for a woman to spend long periods gazing in shop windows, waiting in the lounge of an hotel or lingering over coffee in a restaurant, and, of course, thefts occur in places set aside for ladies where no man may enter without causing an uproar.

In the matter of disguises women have an enormous advantage over men. A retired C.I.D. superintendent once wrote, “Give a woman detective a shopping bag, and she is disguised at once.”

Policewomen have been known to arrest most men who are drunk and disorderly but their male counterparts are not particularly keen to have women handling the “rough stuff”. Most of the women are content that this should be so though some are sufficiently competent enough to handle offenders through a knowledge of judo which forms part of their police training” (Barlow 1975 p294).

If this was the attitude of senior management of the day setting the cultural tone of the organisation, little wonder others in the organisation followed the cue. Yet the situation was about to change with calls for reform becoming ever more strident.

The first serious call to end occupational discrimination against policewomen in New South Wales came at the 1975 Annual Conference of the NSW Police Association. It was International Women’s Year and it was pointed out that policewomen in Europe and North America were well ahead of their New South Wales counterparts in terms of operational roles and duties. Also the Bloch and Anderson report “Policewomen on Patrol” had been released in the United States the previous year clearing away many cultural beliefs and myths about the suitability of women to perform police duties. However, policewomen in the NSW Police Force still faced limited promotion opportunities and other workplace limitations.

The centrepiece of this call was an address to the Conference by Patricia Campbell, the executive officer of the NSW Committee on Discrimination in Employment. The situation she described raised considerable attention (Campbell 1975 p194). In 1974 there were about 8500 policemen in the NSW Police Force, but only 123 policewomen. She pointed out the effect of the quota system on opportunities for policewomen in the NSW Police Force. At a time when 40 percent of the NSW workforce was female, only 1.5 percent of the NSW Police were female. She then discussed rank proportions in the police for policemen and policewomen. In the comparison of Commissioned ranks to Sergeants, the male ratio was 1:7.8 and the female ratio was 1:9 (this ratio did not reflect the actual numbers of policewomen in the Force as opposed to the number of policemen as the number of policemen, together with the opportunity for promotion, was much greater). Yet in the ratio of Sergeants to Constables, the male ratio was 1:2.3 whereas for females it was 1:12.5 (Campbell 1975 p194). This clearly indicated that the chances of a female being promoted from Constable to Sergeant was much less than a male achieving the same promotion, bearing in mind that the seniority lists of the day were not completely integrated until 1978 and policewomen did not start to serve on general duties (patrol) until 1976 and were not directly posted there until 1980.

Campbell then focussed on the arguments used as to why policewomen should not have a larger role in the NSW Police Force. They included:

- Women cannot supervise or lead

- Women cannot be used in pub brawls

- It wouldn’t be nice for women to hear swear words

- Policewomen shouldn’t carry guns (Brien 1996 p138)

These were not just the thoughts of a few Neanderthals who had lost touch with reality in a changing world. They tended to reflect the broader social thinking of the day. Even one of the greatest reformist police thinkers of the late 20th Century, John Avery, who was later to become Commissioner of the NSW Police from 1984 to 1991 and preside over a range of critical reforms in the organisation, tended to think along some of these lines (Nixon & Chandler 2011). Commissioner Avery’s reforms included a rapid increase in the number of policewomen in the Force, the regionalisation of police command in New South Wales and the changing of the title of the organisation from “NSW Police Force” to “NSW Police Service” in 1989.

In his formative book “Police. Force or Service?” Avery (1981 p81) describes the need for policewomen in a police organisation and argues for a rethink of the current position, but then goes on to limit their role somewhat by saying “there are important reasons why it is advantageous that the great majority of police should be men, muscular, fit and intelligent men at that.” Avery then calls for a re-evaluation of the role of policewomen at that time and describes the reality of police work being a large percentage of non violent calls for service, but draws a line at engaging policewomen in duties that could involve violent confrontations. He also argues against two women car crews and stipulates the need for back up vehicles to be available where mixed crews are rostered on shift. His final proposal was for policewomen to be taken off general duties (patrol) policing after their initial probation, for transfer to a specialist squad, unless they specifically asked to remain there.

Following on from the 1981 Lusher Report into police recruitment and education in New South Wales, from the mid 1980s Commissioner Avery was responsible for many reforms that overhauled recruitment and training in the NSW Police Force and set the groundwork for the modern organisation that exists in the 21st Century. In 1986 height restrictions were abandoned, together with the updating of educational and physical standards. The main thrusts of these reforms were to increase the overall representation of the community in the NSW Police Force and increase the proportion of women in the ranks (Chan 1997 p129).

When put in the social context of the day, these were radical proposals, as they went against what had been accepted practice in most police forces that deployed policewomen at that time and they need to be viewed in that light. As previously stated, Commissioner Avery presided over a large increase in the strength of policewomen in the NSW Police Force, not just in terms of actual numbers, but also in terms of proportional representation. The position of policewomen in the NSW Police Force was very much advanced at the end of his tenure than at the beginning.

This dramatic change in cultural thinking has a comparison in another place and time and it stems back to the changes that were forced on American Society by the Civil war from 1861 to 1865. In late 1864 as the Confederacy was facing defeat, President Jefferson Davis called on the Confederate Congress to consider a Bill that would permit the arming of African-American slaves to defend the Confederacy. The Bill was not passed. One Confederate Congressman, Howell Cobb, saw the implications of the proposal clearly:

“You cannot make soldiers of slaves or slaves of soldiers. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong” (Keegan 2009 p292 – 3).

Maybe, by women making good police officers, then it was being clearly shown that the current theory of gender roles, as it applied to policing and the wider community, was wrong. It was a huge shift in social culture that was taking place, not just policing culture and the ramifications were beginning flow across many workplaces and against differing scales of resistance.

Austin (2000) describes her experiences in the NSW Police in the mid to late 1980’s, being refused access to training “in case she had a baby and resigned”, being “kept indoors” in the police station if anything violent happened (even though she had served in the Australian Regular Army before joining the NSW Police and having worked as a Social Worker). These limits on her development impeded her progression within the organisation over time. However, she makes a valid point when discussing the benefits to bringing female leadership traits into the police organisation and culture:

“The masculinised organisations we work for are unnatural and unbalanced. We need to bring to these organisations the range of skills women have been allowed to offer in private – competence, endurance, love, compassion, understanding and the ability to nurture to excellence. These organisations have an obligation to allow us to operate within our femininity in whatever individual form we possess it” (Austin 2000 p139).

This “protection” and “stereotyping of role” was certainly an observation I made in my early career. In large crowd control situations, many a young policewoman found herself looking after lost children, even though she may not have any children of her own or any experience in looking after children. The stereotype was compounded by the fact that there may have been many more qualified police fathers available, but who were deployed to work in the crowd as child minding was “women’s work”.

Duberly (1981 p17) also supports this view that policewomen were very restricted in their career aspirations and states the following with regard to the status of policewomen in the newly integrated workplace:

“Policewomen, as tokens in the male dominated occupation of general duty police, face a number of dilemmas which arise from the apparent conflict between sex role norms and occupational role norms. They face performance pressures, isolation from co-workers, tests of loyalty and entrapment in stereotype roles. They are expected to out-perform others and are closely watched for any sign of weakness and yet at the same time are expected to conform to typically feminine behaviour. They may be labelled with such labels as ‘bitch’ and ‘lesbian’ for failure to act in stereotypic ways.”

Yet, oddly enough, some of the greatest critics of policewomen are other Policewomen. A survey of policewomen’s stereotypes of policewomen generally showed a very critical view being displayed by serving policewomen (especially those who had served for some time) of recruitment standards, personal attributes and moral attitudes of newer recruits (Sutton 1995 p154).

This was also coupled with the perceived male stereotypes of policewomen held by policewomen. Many policewomen still believed that the male stereotype of policewomen was extremely negative although this was gradually changing (this survey was carried out in 1995), 15 years after the general deployment of policewomen to patrol policing and almost 20 years after the Darlinghurst experiment in 1976 (Sutton 1995 p153; Sutton 1995a p46).

As She Climbs the Promotional Ladder

Barbara Etter (2008), a former New South Wales policewoman, Director of the Australasian Centre for Policing Research, Superintendent of the Northern Territory Police and now Assistant Commissioner with the Western Australia Police looks at another aspect of discrimination against women in the workplace as it applies to policing during the promotion process. She points out that junior policewomen have to contend with sexual harassment, bullying and gender discrimination, together with the need to prove they can do the job, but as policewomen become more senior and take on supervisory and managerial positions a whole range of new issues confront them, such as cultural politics, exerting authority and influence effectively and workplace professional relationships. Austin (2000 p135) supports her in this view and goes on to state that often, in order not to damage their career prospects policewomen are forced to discount the frequency and effect of this harassment .

Policing has traditionally had a militaristic, masculine type of leadership which favours “heroic” leadership styles rather than the quieter, less obtrusive styles favoured by modern leaders (Etter 2009a). Policewomen have not yet developed what Etter describes as “critical mass” in senior positions to make any difference to this mindset. Etter discusses the nature of power within police organisations in the context of Position Power and Personal Power, pointing out that women tend to use personal power i.e. influence derived from task expertise, friendship, persuasion and charisma rather than position power based on legitimate authority , control over resources, rewards and punishments and control over the organisation. She also points out that personal power tends to be more transformational than transactional, that is being good at being able to lead change rather than just the day to day organisational functioning.

Etter also makes the point that there are a range of obstacles to women acquiring power in the policing workplace namely; their refusal to identify themselves as leaders, the pressure for them to conform, getting support, maternalisation of women in authority and loss of self, body and sexuality in the role. Austen (2000 p131) points out that policewomen often lack the power networks and contacts that aid them in advancement within the organisation. This is made even more so by the taboo against women and men being friends in the workplace. This becomes critical in a male dominated workplace, with few women at senior levels as senior policewomen have relatively few friends in which to confide and who can provide a support network.

Another interesting phenomenon in women’s own views on their leadership is the “impostor syndrome” articulated by Dr Susan Harwood (2009). This is where some women who win leadership roles believe they do this by a “fluke” or accident rather than as a result of their skills and abilities.

Etter raises the valid point that many men are threatened by women with power and this leads to attempts to undermine them in the workplace. This is graphically illustrated by the later Case Study on Christine Nixon when she became Chief Commissioner of the Victoria Police in 2001. What policewomen in senior positions have found is that they have not been subject to sexual harassment but rather to being undermined by their peers. Christine Nixon certainly found this to be the case with some of her detractors being forced to resign and face criminal sanctions, as will be discussed later in the chapter (Stewart 2010).

Another factor critical to issue of women in leadership roles is the promotion process itself. In 1988 the promotion system in the NSW Police Force moved from seniority to merit based, yet it had relatively little impact on the numbers of policewomen achieving higher rank. There were some historical reasons for this, but in some cases it came down to the type of promotion criteria and selection process. The surveys of policewomen carried out in the mid 1990s indicated that the major concern was the nature of the promotion system as it existed then and how it impacted on the long term career paths of policewomen (Sutton 1995a p46). Interestingly, the same research showed that policewomen, generally, believed they had the same opportunities as policemen and those applying for promotion were achieving interviews (81%) and promotions (75%), yet only 17% of those eligible to be promoted had applied by 1995 and it was a source of concern (Sutton 1995a p38).

In 1997 the NSW Police Force moved from an application/interview model to an assessment centre based model for all ranks from the level of Sergeant. It was also proposed that consideration be given to the composition of the panels, together with the type of assessment instruments used, with regards to the number of policewomen and police from minority backgrounds, to give fairness to the selection process (NSW Police Service 1996; The Women in Policing Ministerial Working Party 1996 Appendix E). The aim here being to minimise the effect of “organisational cloning” through the bias of promotion panels.

The NSW Police Force did not adopt a “quota” system of numbers of each group to be represented at each level, as this has been regarded as leading to possibly unqualified people being promoted. However there has always been targeted recruitment and positive discrimination to ensure that all qualified people are encouraged to apply for development and promotion opportunities (NSW Police Service 1996). This situation seems to be changing with an increase in the number of women applying successfully for promotion in recent years (Prenzler et al. 2010; Prenzler & Fleming 2010). This seems to reflect a broader trend across Australian policing as a whole, with research showing increased numbers of policewomen being promoted to supervisory and commissioned ranks between 2003 and 2008 (Prenzler & Fleming 2010).

Another side to this is the differing attitudes of policemen and policewomen when it comes to promotion. Sutton (1995a p5) studied why women and men join the NSW Police Force. Her findings for women were that the range and variety of work was the paramount factor (90%) with the opportunity to help people next (88%). The prestige of the police and the lack of job opportunities were not considered important factors in a policing career (72% were not concerned by this).

Against this, 88% of policemen rated career prospects as a key factor and only 18% were not worried about lack of career opportunities. Security of employment and excitement rated higher at 95%. The traditional status and power of the police role was a key underlying factor for men. These factors do not show their impact on informal leadership in the workplace, which occurs at all levels, but is indicative of issues in the formal leadership/promotion situation.

To put this into proper context, it is also important to make comparisons to similar organisations outside of policing in Australia. A recent survey found that the armed forces had similar rates of women in senior leadership positions of or above Lieutenant Colonel or equivalent. The Royal Australian Navy rated 4.8%, the Army 4.5% and the Royal Australian Air Force 7.4%. Total numbers of women in the organisations equated to 18.2%, 9.7% and 16.5% respectively (McPhedran 2009).

Interestingly, the civilian workplace in Australia rated nearly as badly, even though it could be expected that the ratios would be much improved. In 2008 only 8.3% of board members in Australia’s top 200 companies were women, down from 8.7% in 2006. Only 2% of these company boards were chaired by women and 50% of these companies had no women on their boards at all (Korporaal 2009). Also women only made up 5.9% of senior executives in these top 200 companies (Dunlevy 2009).

It would seem that these concerns of gender disadvantage, representation and opportunity are drawing worldwide attention. The French Government recently passed affirmative action legislation requiring that the representation of women in corporate boardrooms in France be raised from below 10% to 40%. This follows in the footsteps of Norway which introduced similar legislation in 2003. Spain, where women fill only 4% of corporate board position, has introduced a voluntary code of practice although the effect of this is yet to be seen (Alberici 2010).

As an overall picture, Rachelle Irving (2009) makes some interesting observations on the “Career Trajectories” for women in policing in Australia in her study for the Australian Institute of Criminology. Her research showed that by comparison to overseas, proportionately more women were joining policing in Australia since the early 1990s. Her research showed that in 1996 13.5% of Australian police were female and by 2006 the percentage had risen to 23%.

She tracked cohorts of policewomen in a number of different State Police Services who joined in 1991 and compared them to their male counterparts who joined at the same time. In New South Wales she discovered that although fewer policewomen attained senior (Commissioned) rank, those that did achieved it in less time than their male counterparts. Also policewomen were less likely to be dismissed due to misconduct or die on duty, but were less likely to make it to general retirement age, but rather, they would leave for other reasons including medical retirement (2010 pp3-4).

She also found that one of the key barriers to promotion for policewomen was still a lack of appropriate experience to gain senior rank although she noted that these negative organisational barriers were slowly changing (2009 p5). Other barriers to career progression included issues with shift work, child care and maintaining a healthy life/work balance. Her final observation was that these issues are not peculiar to the Australian policing environment and have a common ring in other comparable organisations in Australia and overseas.

It would seem that police organisations still have a significant way to go in this area. At a time when retaining skilled, experienced staff is becoming even more crucial, these are critical policy areas.

The Darker Side of Culture

Behind the managerial issues and discussions lurked another, darker side to the increase of the numbers of policewomen in the NSW Police Force. This dark side was summed up neatly by a former NSW Detective named Deborah Locke when she wrote of her experiences in the NSW Police after 1984:

“Times were a’ changing. Not only women were going out onto the streets, but ‘ethnics’ and gays were also being welcomed into the ranks. Sadly, we were only welcomed in on paper. When it came to the real world, brutal and violent treatment was dished out to people of difference.” (2003 p10)

Locke also describes the resistance of police wives to their husbands working with policewomen, alone and unchaperoned in the early hours of the morning. She also describes the cultural issues of becoming a Detective in New South Wales in the mid 1980s. As Locke states, you did not apply, you were invited and you had to fit the mould (2003 p20).